Three Kingdoms of Scandinavia

In my final year at the Architectural Association, I created three humorous speculative fictions on the future of Scandinavian cities, seamlessly blending Norse mythology with social media and the looming climate crisis.

Waldrasil

The princess on the pea is sovereign in a tyranny of care

Princess Estelle was but 13 years old when the Swedish Netflix series, Young Royals, third season was released. The focus of the story shifted to the crown princess of Sweden, after the former protagonist, her gay older brother, was forced to abdicate. The show’s creators were criticized for their lack of faith in the Swedish people’s ability to accept a gay king. Desperate to make amends, they reached out to climate activist Greta Thunberg, asking her to star in the show and use it as a platform to spread her message.

The show became– as one would expect– a global sensation. It also brought attention to the real-life Princess Estelle, who became an overnight celebrity. Under media scrutiny, the Princess naturally modelled herself after her fictional counterpart. Tragedy soon struck as her mother, the Queen, perished in a car crash while being chased by paparazzi. Her driver was said to be under the influence of Fentanyl and was of Somali origin. Polling data suggested that the far-right party surged in popularity after the funeral and the young party leader demanded a wall be built along the country’s borders to keep out the growing number of climate refugees.

In the following year, the right-wing party won a majority in the election, and a crisis meeting was held between the sitting parties and the young Princess. They decided to negate the vote and use military force to maintain their power. In response, the palace was stormed by a frenzied mob, and the Princess barely escaped to Drottningholm, an island on the outskirts of Stockholm, where a wall was erected to protect her.

Peace was enforced, and the young Queen was coronated. For the occasion, a seed bank was constructed on the Queen’s Isle, symbolling the primacy of climate preservation. The seed bank preserves the potential of life, rather than actual biodiversity. The island was a walled garden which was tended by the Queen’s maiden who bred sterile and plentiful crops through a process of emasculation, which was used by the country’s farmers.

A second wall sprung up around Stockholm, protecting the political and bureaucratic establishment after the government headquarters was destroyed after a van had parked outside with a homemade bomb made of fertilisers. The city became free of cars, its streets and public spaces turning into giant verdant gardens. The area housed care homes, nurseries, and hospitals.

A third, more perforated wall, forms around the suburbs of the city. It is a quiet area composed of families provided for by a generous child support system that the Queen had announced to boost the stagnating birth rates. With artificial insemination gaining blanket legalisation, many women chose to become single mothers as they were able to be full-time parents without the support of a partner.

The fourth and final wall was built to fulfil the remaining, right-wing citizens’ original wish for a wall around the entire country. It housed a predominantly single male population who were responsible for industry and food production. They were encouraged to visit sperm banks regularly where they were given access to AI-generated pornography based on the women of Waldrasil. They never knew whether they became fathers or not. Their children lived like Schrodinger’s Cat, inspiring their father’s loyalty to the tyranny of care.

Niflhavn

Whose citizens trade in the mead of poetry

A group of Danish influencers ventured to raise awareness of the ongoing climate emergency by living on floating islands in the Arctic Ocean for a year. They documented the melting poles and dying wildlife sharing it with a huge following, however, it garnered little attention. The group then resorted to the tried and tested strategy of ‘gossip’ by starting a popularity contest. It became embroiled in the culture war within the ecological movement, with commentators questioning whether to adopt neoliberal schemes for the green movement.

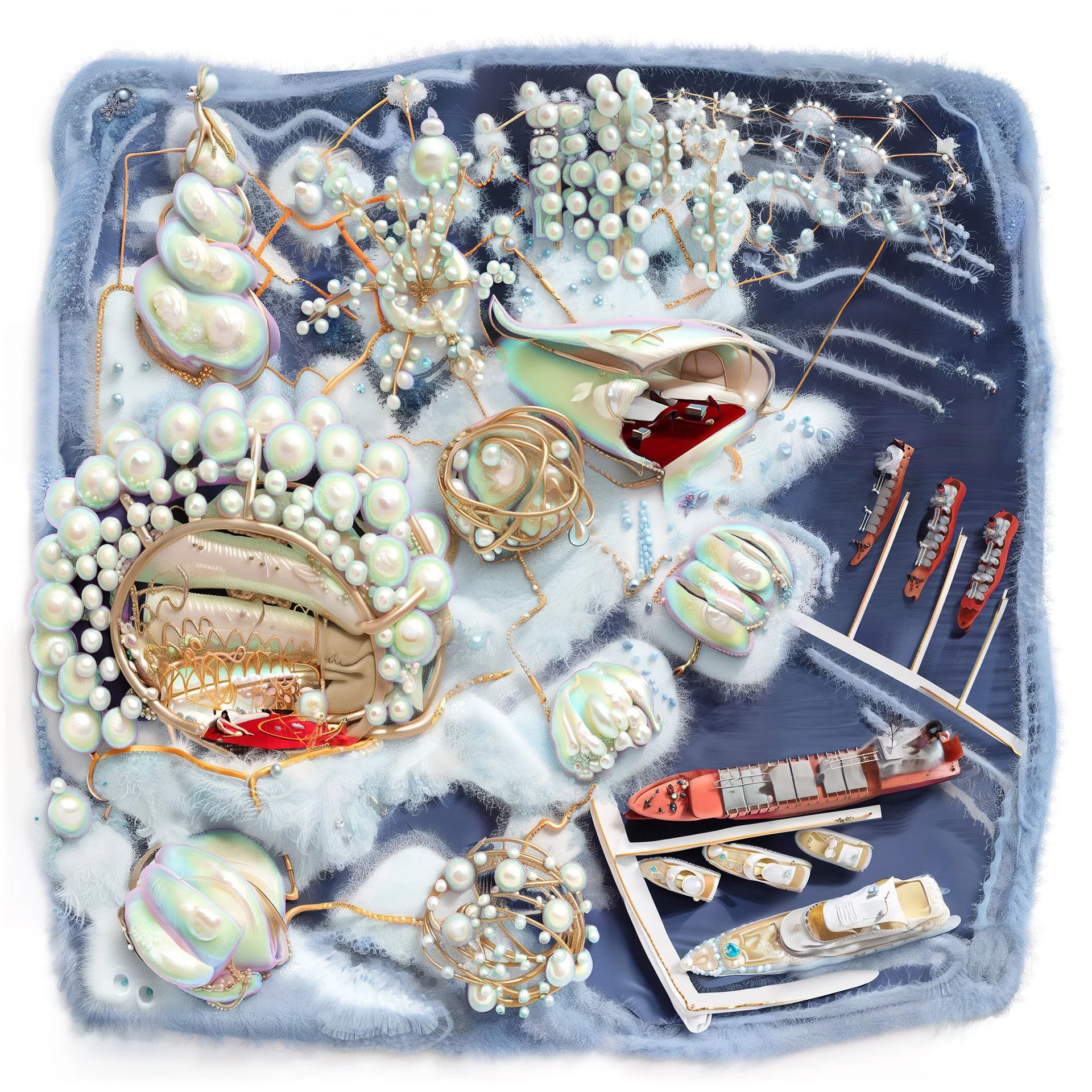

The sensation could not stop after one year. More influencers flocked to the growing floating city, clustering around its many islands of varying sizes. The founder of Ethereum, Vitalik Buterin, approved of the venture, and the low-carbon cryptocurrency became the city’s currency. Inhabitants earned huge sponsorships and benefited from a surge in Ethereum value. Everyone was tokenised, allowing family, friends, and fans to directly invest in them.

The city of Niflhavn was a never-ending bacchanalian soap opera watched and provided for by a global audience. During every winter solstice, the dark continent is lit up with a giant festival financed by the highest valued induvial who is forced to spend their fortune on sending gifts to the city’s global fanbase. The maelstrom at the top of the pyramid ensured a constant shifting of wealth as well as the continued success of the venture.

The various vessels making up the city vary from floating favelas providing precarious housing for the service workers on the outskirts of the city to container ships and luxury yachts and aircraft carriers at the centre. The city’s many islands constantly shifted, with the city centre changing along with various trends and influences. If one failed, one is simply shifted out.

Draugrheim

Seventh father’s rule

A great commotion was stirred when plans for a new hydroelectric power plant were announced at the base of Norway’s second-tallest mountain. An enormous glacier was melting at an alarming rate and the power companies were eager to source the green energy that was coveted by the European market. However, the proposed dam would cover the valley between the two tallest mountains of Norway, and ruin hiking paths that held fond memories for the citizens. Giant protests erupted, and a stalemate ensued between the two sides as the site was settled by protestors.

The high court finally declared the legality of the dam. At this crucial moment, Magnus Midtø, a former world climbing champion and youtuber, decided to draw attention to the cause by free soloing (climbing without ropes) the cliffside of the mountain. The world watched with bated breath as Magnus fell to his death on the first Friday of April. Three days later, the high court was pressured to revoke the order. Magnus became a martyr for the cause, and a burial mound was raised around him at the foot of the mountain.

Despite the protest coming to an end, the city of Draugrheim continued to thrive. It had become an iconic symbol of radical environmentalism, and people from far and wide made the pilgrimage to pay homage. Over the years, the city formed a chain around the mountain, and eight other martyrs were buried at regular intervals along its side, each with their own burial mound. The houses formed communities around these sites, and resources were shared along the chain of houses. A strict moral code was enforced to ensure everyone’s cooperation and neighbourly support.

As time went on, the citizens themselves built a power station on their sacred river. It was much smaller than the one originally proposed as it was only intended for their own modest usage. The animistic worship of the river suited this symbiotic relationship, even though the rest of the country had little to gain.